Exploring AArch64 assembler – Chapter 8

In the last chapter we saw how to call a function. We mentioned a special memory called the stack but we did not delve into it. Let’s see in this chapter how we can use the stack and why it is important in function calls.

Function calls

When we call a function, that same function can call other functions and so on. It is a bit like if we suspended the execution of a function to execute another one. The constraint here is that we always resume the execution when the called function ends. This is, we return always in the inverse order of the function calls. As a consequence, we can see the number of function calls active at some point as a stack (like a stack of plates).

This property is important because a function, say F, may need to keep some temporary memory. When F calls another function G, we want this memory be preserved when we return from G. Given that the activations of the functions follow a stack-like pattern, it seems natural that the temporary memory used by functions also follows this schema. This schema is so common that most architectures provide a specialized mechanism for this kind of «temporary memory associated to the activation of functions». That memory receives the name of stack basically because it follows a stack discipline: an element that is in the stack can only be removed when all the elements added after that first element have been removed.

The stack and convention call

Since the stack memory behaves like a stack, the only interesting thing we care about is its top element as in practice the stack is never empty. Since the stack is memory and memory is accessed using addresses, the top of the stack is an address. This address is stored in a special register called sp for stack pointer. Changing the value of sp changes the size of the stack. The whole stack memory ranges from the stack base, which is not kept anywhere and is usually conventional, and the stack pointer.

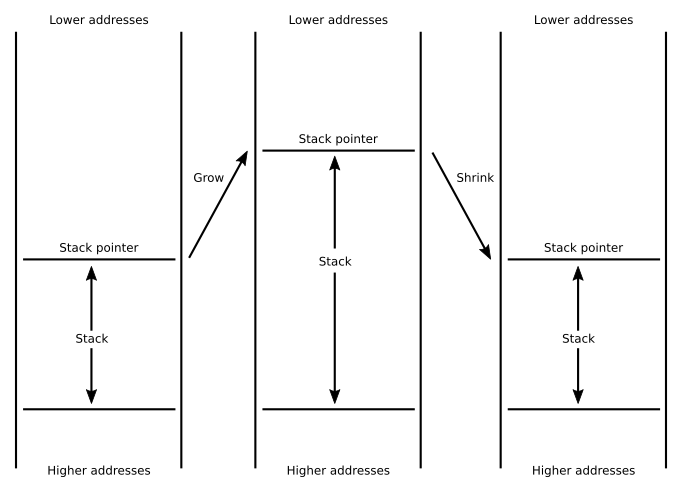

The stack has, then, two basic operations: it grows and it shrinks. Growing is done when we need to add new elements to the stack. Shrinking is done when we want to remove such elements. A function will typically grow the stack to keep temporary memory and it will shrink, by the same amount of elements, the stack before the function returns. This way, when returning from a call, the caller will have the stack as it was right before the call.

We have not specified how the grow and shrink operations are actually implemented. An architecture can decide make the stack grow towards higher addresses (and shrink towards lower addresses) or make the stack grow towards lower addresses (and, hence, shrink toward higher addresses). AArch64 chooses the latter, so to grow the stack we will just reduce the value in sp and to shrink it we will increase it.

The convention call of functions in AArch64 also dictates an additional constraint on the values that sp can take. Without too much details, at any point we use the sp (except for strictly growing or shrinking it) its value must be a multiple of 16. This means that the addresses kept in sp will be always aligned to 16-bytes.

Operating the stack

The operation of adding an element of the stack is commonly known as a push. A push does two things: it first grows the stack as many bytes as the size of the element and then does a store to the top of the stack. The inverse operation, removing something from the stack, is known as a pop. In this case first a load from the top is done to retrieve the value and then the stack is shrunk as many bytes as the size of the element removed. Recall that grow will mean subtracting the number of bytes from sp and shrinking it will mean adding the number of bytes to sp. Sometimes we do not want to retrieve the value, in this case we simply shrink the stack.

We could implement push and pop using a combination of sub/str and add/ldr instructions. And it could work but these operations happen very frequently so a combination of two instructions for each looks inefficient. Luckily we can cleverly use addressing modes to grow and shrink the stack at the same time that we perform a store or a load respectively.

If you recall chapter 5, we saw two addressing modes called pre-indexing and post-indexing. In these modes there is a base register plus an offset. In a pre-index mode the computed address is the offset added to the value of the base register. In a post-index mode the computed addres is just the value of the base register. Both modes update the base register with the value of the offset added to the value of the base register. These modes are useful when accessing contiguous memory, and the stack memory elements are a kind of contiguous memory.

With this insight, now we can implement a push using a store that uses pre-indexed mode with sp as the base register. This works because we want the address used for the stored be the new storage and then we want to update sp to point to that new memory. For instance, we can preserve the value of x8 in the stack doing this:

// Keep register x8 in the stack

str x8, [sp, #-8]! // *(sp - 8) ← x8

// sp ← sp - 8

Note that we use an offset of 8 because x8 is a 64-bit register. The offset is negative because in AArch64 the convention tells us to use a downwards growing stack.

A pop, conversely, is implemented using a pre-indexed address mode. For instance, we can restore the preserved value of x8 doing this:

// Restore register x8

ldr x8, [sp], #8 // x8 ← *sp

// sp ← sp + 8Note that the offset in this case is positive, because now we are shrinking the stack.

Well, this could work but we're not quite there yet. The reason is that the convention tells us to keep the stack aligned to a multiple of 16. Assuming it was originally like this, just doing a single ldr/str will break this property very easily. One option is making sure the stack is still aligned by using additional add/sub instructions. Another option is making sure we push and pop pairs of 64-bit registers. As each register takes 8-bytes, two of them will take obviously 16-bytes. If we push in pairs the stack remains aligned in a single instruction. To do this, AArch64 provides special load/store pair instructions called ldp and stp. These instruction receive two registers and a single addressing mode. The registers are loaded/stored as consecutive elements of the address computed by the addressing mode.

For instance, the following sequence:

str x11, [sp, #-8]! // *(sp - 8) ← x11

// sp ← sp - 8

str x8, [sp, #-8]! // *(sp - 8) ← x8

// sp ← sp - 8can be rewritten as

stp x8, x11, [sp, #-16]! // *(sp - 16) ← x8

// *(sp - 16 + 8) ← x11

// sp ← sp - 16

As you can see the first register in the instruction will be the one in the top of the stack. The second register is just stored contiguously after that (towards the bottom of the stack). A similar thing happens with the corresponding ldp implementing a pop of these two registers.

ldp x8, x11, [sp], #16 // x8 ← *sp

// x11 ← *(sp + 8)

// sp ← sp + 16

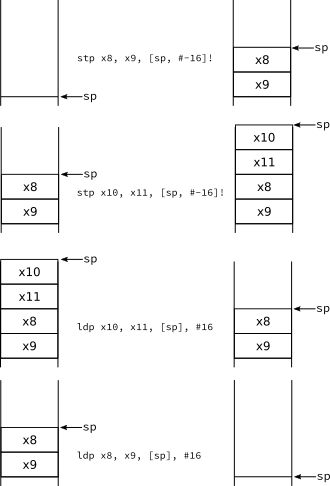

As long as we use the same order of registers inside ldp and stp we are fine. Note that this is a stack, so the first elements we put must be the last to leave. This means that if we want to keep and restore, say, x8, x9, x10 and x11, the right order is the following.

// push x8, x9

stp x8, x9, [sp, #-16]! // *(sp - 16) ← x8

// *(sp - 16 + 8) ← x9

// sp ← sp - 16

// push x10, x11

stp x10, x11, [sp, #-16]! // *(sp - 16) ← x10

// *(sp - 16 + 8) ← x11

// sp ← sp - 16

...

// pop x10, x11

ldp x10, x11, [sp], #16 // x10 ← *sp

// x11 ← *(sp + 8)

// sp ← sp + 16

// pop x8, x9

ldp x8, x9, [sp], #16 // x8 ← *sp

// x9 ← *(sp + 8)

// sp ← sp + 16

So basically what is pushed the first is popped the last. Or similarly: the order of pops must be the opposite as the order of pushes.

Fibonacci

The archetypical example when explaining recursion is computing the Fibonacci numbers doing a direct translation of the formula. This is not an efficient way to compute such numbers (in the rare case you actually need them) but makes for a simple example involving recursion. Recursion to work many times requires a stack (except for a subset of specially recursive functions that don't) so this will showcase how to manipulate it.

We will write a program that will ask for a number n and will compute the n-th Fibonacci number. Let's write the main function first.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

.data

msg_input: .asciz "Please type a number: "

scanf_fmt : .asciz "%d"

msg_output: .asciz "Fibonacci number %d is %ld\n"

.text

.global main

main:

stp x19, x30, [sp, #-16]! // Keep x19 and x30 (link register)

sub sp, sp, #16 // Grow the stack because for a local

// variable used by scanf.

/*

Our stack at this point will look like this

Contents Address

| var | [sp] We will use the first 4 bytes for scanf

| | [sp, #8]

| x19 | [sp, #16]

| x30 | [sp, #24]

*/

// Set up first call to printf

// printf("Please type a number: ");

ldr x0, addr_msg_input // x0 ← &msg_input [64-bit]

bl printf // call printf

// Set up call to scanf

// scanf("%d", &var);

mov x1, sp // x1 ← sp

// the first 4 bytes pointed by sp will be 'var'

ldr x0, addr_scanf_fmt // x0 ← &scanf_fmt [64-bit]

bl scanf // call scanf

// Set up call to fibonacci

// res = fibonacci(var);

ldr w0, [sp] // w0 ← *sp [32-bit]

// this is var in the stack

bl fibonacci // call fibonacci

// Setup call to printf

// printf("Fibonacci number %d is %ld\n", var, res);

mov x2, x0 // x2 ← x0

// this is 'res' in the call to fibonacci

ldr w1, [sp] // w1 ← *sp [32-bit]

ldr x0, addr_msg_output // x0 ← &msg_output [64-bit]

bl printf // call printf

add sp, sp, #16 // Shrink the stack.

ldp x19, x30, [sp], #16 // Restore x19 and x30 (link register)

mov w0, #0 // w0 ← 0

ret // Leave the function

addr_msg_input: .dword msg_input

addr_msg_output: .dword msg_output

addr_scanf_fmt: .dword scanf_fmt

The main program first asks the user for a number using printf, reads a 32-bit integer from the input using scanf. With that number we call fibonacci (we will see its code later) and then just print the result for the given number, again using printf.

In lines 3 to 5 we define a few strings that we will need for the printf and scanf calls. The directive .asciz means "emit these characters as ASCII bytes and add a zero byte at the end". The zero byte is required by C routines that use it to tell where the string ends. The marker %d in scanf_fmt means "read an integer and store its value as a 32-bit signed number in the given address" (you will see this in the call of scanf below). The markers %d and %ld in msg_output mean "print an integer as a decimal number of 32-bit/64-bit" respectively.

As this function calls another function it has top keep the value of x30, line 11. Recall that executing a bl instruction will change x30 to be the address of the instruction after that bl. Also, ret instruction uses x30 to know where to return. So if our function calls another function it must keep x30. As we have to keep the stack aligned to 16-bytes, storing x30 is not enough so we will also keep another register even if we do not use it. Conventionally we will use x19 as it is the first callee-saved register

As mentioned above, scanf reads an integer from the input and stores it in some memory. We could use a global variable for that but we can also use the stack, but first we need to make room in the stack. So we grow it by 16-bytes, line 12. Actually we only need 4 bytes but recall, the stack must be kept 16-byte aligned, so yes, we will waste 12 bytes in this case.

Then we do the first call to printf, lines 25 to 26. This call only receives a parameter, which is the address of the string msg_input. So we simply load the address to w0 and then bl to printf.

Now we do the call to scanf. This call receives first the format of the input read (the string %d that we have in scanf_fmt) and the address of the memory where we will store the result of the scanf. The first parameter is the address of scanf_fmt so we load it in w0, line 32. The second parameter is the address where we want scanf to store the read integer. In this case we will use the first 4-bytes in the address pointed by sp. So we simply copy the value of sp in x1 using mov, line 30. Now with everything in place we can do the call to scanf, line 33. Note: the order in which we set up the registers for parameters is usually not very relevant (except for those cases where it might make things easier, of course).

Now after scanf has returned in the top of the stack, pointed by sp, we have an integer that we can pass to fibonacci. So we load it, line 37, in w0. And we're now ready for the call to fibonacci, line 39.

Our fibonacci function receives a 32-bit integer as a parameter and returns a 64-bit integer as the result. The calling convention of AArch64 says that for the parameter we have to use w0 and return it in x0. So to prepare the call to the final printf, we have to make sure our 64-bit number is in the right register, so we copy x0 (set by the fibonacci call) to x2, line 43, and then we load again from the stack the value we passed to fibonacci, but this time we load it into w1, line 45. Lastly we load into w0 the address of msg_output. Now we can call printf to show the results of our computation.

Now the only thing that remains to do in this function is to do clean up. We shrink the stack that we grew for the local variable, line 49, and then we restore the values of x19 and x30 (the link register, which was modified by the bl instructions), line 50. Now we can return, line 52, but since this is the main and returns an integer, we just make sure w0 is set to zero just before returning, line 51.

Now we can see the code of the fibonacci function.

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

fibonacci:

// fibonacci(n) -> result

// n is 32-bit and will be passed in w0

// result is 64-bit and will be returned in x0

stp x19, x30, [sp, #-16]! // Keep x19 and x30 (link register)

stp x20, x21, [sp, #-16]! // Keep x20 and x21

/*

Our stack at this point will look like this

Contents Address

| x20 | [sp]

| x21 | [sp, #8]

| x19 | [sp, #16]

| x30 | [sp, #24]

*/

cmp w0, #1 // Compare w0 with 1 and update the flags

ble simple_case // if w0 <= 1 branch to simple_case

// (otherwise continue to recursive_case)

recursive_case: // recursive case

// (this label is not used, added for clarity)

mov w19, w0 // w19 ← w0

// Set up call to fibonacci

// fibonacci(n-1);

sub w0, w0, #1 // w0 ← w0 - 1

bl fibonacci // call fibonacci

mov x20, x0 // x20 ← x0

sub w0, w19, #2 // w0 ← w19 - 2

bl fibonacci // call fibonacci

mov x21, x0 // x21 ← x0

add x0, x20, x21 // x0 ← x20 + x21

b end // (unconditional) branch to end

simple_case:

sxtw x0, w0 // x0 ← ExtendSigned32To64(w0)

end:

ldp x20, x21, [sp], #16 // Restore x20 and x21

ldp x19, x30, [sp], #16 // Restore x19 and x30 (link register)

ret

Similar to the main function we first start by keeping all that must be restored upon leaving the function. So we keep x19, x30 and x20 and x21, lines 64-65. In contrast to the main function, where x19 was not used but we kept it and restored it to keep the stack 16-byte aligned, we will use all the preserved registers this time.

The fibonacci function is actually a sequence of numbers Fi defined by the following recurrence:

- F0 = 0

- F1 = 1

- Fn = Fn-1 + Fn-2, where n > 1

This means that fibonacci(0) and fibonacci(1) just return the parameter 0 and 1 respectively, the simple case. Otherwise fibonacci(n) has to add fibonacci(n-1) and fibonacci(n-2) to compute the result.

In order to tell whether this is the simple case or not, we just compare w0 with 1, line 75. If w0 ≤ 1 then this is the simple case and we branch to it, line 96. In the simple case we simply extend w0 from 32 to 64 bits, line 96. The instruction sxtw is in practice like a move that also extends (and the name of the instruction is deliberately the same as the extending operators we saw in chapter 3).

For the recursive case, we first need to make sure we will not lose the value of w0 because this is a caller-saved register meaning that its content will be lost after a function call. So we keep it in register w19, line 81, which is a callee saved register, and we already preserved it at the beginning of the function. That said we have not lost the value of x0 already, so we can still use it to compute the parameter for fibonacci(n-1), so we subtract 1 from x0, line 84. Then we do the call, line 85. After the call we want to gather the result, so we will keep it in a callee-saved register, this time x20, line 86.

For the second call to fibonacci, the original value of x0 from which we could compute n-2 has been lost already. However we kept in w19 so we can compute n-2 and store it in w0, line 88. Now we call fibonacci, line 89, and similarly we keep the result in another callee-saved register, this time x21, line 90.

Finally we compute the result of this fibonacci as the sum of x20, which contains the value of fibonacci(n-1), and x21, which contains the value of fibonacci(n-2), line 92. Note that we could have coalesced lines 90 and 92 in a single add x0, x0, x20, but I did in two steps for clarity.

Since we do not want to run the simple case, we just branch to the end of the function, line 93. Like any other function, clean up must be in order, so we restore the registers we kept at the beginning, lines 99 and 100.

OK, let's try our program.

$ ./fibo

Please type a number: 12↴

Fibonacci number 12 is 144

$ ./fibo

Please type a number: 25↴

Fibonacci number 25 is 75025

$ ./fibo

Please type a number: 40↴

Fibonacci number 40 is 102334155Yay! Note that this algorithm is very inefficient so the Fibonacci number 40 will be really slow to calculate. A big number will also overflow 64-bit numbers.

That's all for today.