ARM assembler in Raspberry Pi – Chapter 23

Today we will see what happens when we nest a function inside another. It seems a harmless thing to do but it happens to come with its own dose of interesting details.

Nested functions

At the assembler level, functions cannot be nested.

In fact functions do not even exist at the assembler level. They logically exist because we follow some conventions (in ARM Linux it is the AAPCS) and we call them functions. At the assembler level everything is either data, instructions or addresses. Anything else is built on top of those. This fact, though, has not prevented us from enjoying functions: we have called functions like printf and scanf to print and read strings and in chapter 20 we even called functions indirectly. So functions are a very useful logical convention.

So it may make sense to nest a function inside another. What does mean to nest a function inside another? Well, it means that this function will only have meaning as long as its enclosing function is dynamically active (i.e. has been called).

At the assembler level a nested function will look like much any other function but they have enough differences to be interesting.

Dynamic link

In chapter 18 we talked about the dynamic link. The dynamic link is set at the beginning of the function and we use the fp register (an alias for r11) to keep an address in the stack usually called the frame pointer (hence the fp name). It is dynamic because it related to the dynamic activation of the function. The frame pointer gives us a consistent way of accessing local data of the function (that will always be stored in the stack) and those parameters that have to be passed using the stack.

Recall that local data, due to the stack growing downwards, is found in negative offsets from the address in the fp. Conversely, parameters passed using the stack will be in positive offsets. Note that fp (aka r11) is a callee-saved register as specified by the AAPCS. This means that we will have to push it onto the stack upon the entry to the function. A non obvious fact from this last step is that the previous frame pointer is always accessible from the current one. In fact it is found among the other callee-saved registers in a positive offset from fp (but a lower offset than the parameters passed using the stack because callee-saved registers are pushed last). This last property may seem non interesting but allows us to chain up through the frame pointer of our callers. In general, this is only of interest for debuggers because they need to keep track of functions being called so far.

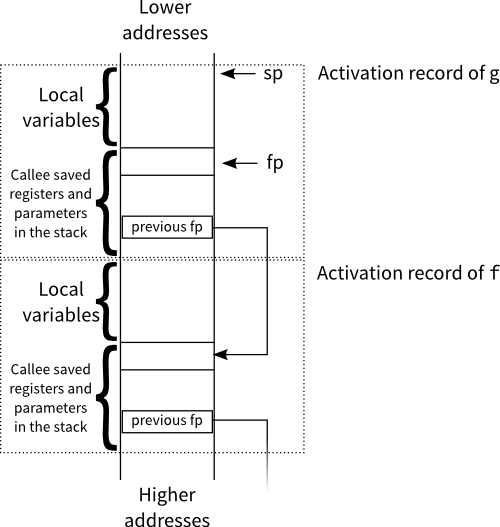

The following image shows how the stack layout, after the dynamic link has been set and the stack has been enlarged for local variables, looks like for a function g that has been called by f. The set of data that is addressed using the frame pointer is commonly called the activation record, since it is a bunch of information that is specific of the dynamic activation of the function (i.e. of the current call).

Static link

When a function calls a nested function (also called a local function), the nested function can use local variables of the enclosing function. This means that there must be a way for the nested function to access local variables from the enclosing function. One might think that the dynamic link should be enough. In fact, if the programming language only allowed nested functions call other (immediately) nested functions, this would be true. But if this were so, that programming language would be rather limited. That said, for the moment, let's assume that this is the case: check again the image above. If g is a local function of f, then it should be possible for g to access local variables of f by getting to the previous fp.

Consider the following C code (note that Standard C does not allow nesting functions though GCC implements them as an extension that we will discuss in a later chapter).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

void f() // non-nested (normal) function

{

int x;

void g() // nested function

{

x = x + 1; // x ← x + 1

}

x = 1; // x ← 1

g(); // call g

x = x + 1; // x ← x + 1

// here x will be 3

}

The code above features this simple case where a function can call a nested one. At the end of the function f, x will have the value 2 because the nested function g modifies the variable x, also modified by f itself.

To access to x from g we need to get the previous fp. Since only f can call us, once we get this previous fp, it will be like the fp we had inside f. So it is now a matter of using the same offset as f uses.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

/* nested01.s */

.text

f:

push {r4, r5, fp, lr} /* keep registers */

mov fp, sp /* keep dynamic link */

sub sp, sp, #8 /* make room for x (4 bytes)

plus 4 bytes to keep stack

aligned */

/* x is in address "fp - 4" */

mov r4, #1 /* r4 ← 0 */

str r4, [fp, #-4] /* x ← r4 */

bl g /* call (nested function) g

(the code of 'g' is given below, after 'f') */

ldr r4, [fp, #-4] /* r4 ← x */

add r4, r4, #1 /* r4 ← r4 + 1 */

str r4, [fp, #-4] /* x ← r4 */

mov sp, fp /* restore dynamic link */

pop {r4, r5, fp, lr} /* restore registers */

bx lr /* return */

/* nested function g */

g:

push {r4, r5, fp, lr} /* keep registers */

mov fp, sp /* keep dynamic link */

/* At this point our stack looks like this

Data | Address | Notes

------+---------+--------------------------

r4 | fp |

r5 | fp + 4 |

fp | fp + 8 | This is the previous fp

lr | fp + 16 |

*/

ldr r4, [fp, #+8] /* get the frame pointer

of my caller

(since only f can call me)

*/

/* now r4 acts like the fp we had inside 'f' */

ldr r5, [r4, #-4] /* r5 ← x */

add r5, r5, #1 /* r5 ← r5 + 1 */

str r5, [r4, #-4] /* x ← r5 */

mov sp, fp /* restore dynamic link */

pop {r4, r5, fp, lr} /* restore registers */

bx lr /* return */

.globl main

main :

push {r4, lr} /* keep registers */

bl f /* call f */

mov r0, #0

pop {r4, lr}

bx lr

Ok, the essential idea is set. When accessing a local variable, we always need to get the frame pointer of the function where the local variable belongs. In line 43 we get the frame pointer of our caller and then we use it to access the variable x, lines 49 to 51. Of course, if the local variable belongs to the current function, nothing special has to be done since fp suffices, see lines 20 to 22.

That said, though the idea is fundamentally correct, using the dynamic link limits us a lot: only a single call from an enclosing function is possible. What if we allow nested functions to call other nested functions (sibling functions) or worse, what would have happened if g above called itself recursively? The dynamic link we will find in the stack will always refer to the previous dynamically activated function, and in the example above it was f, but if g recursively calls itself, g will be the previous dynamically activated function!

It is clear that something is amiss. Using the dynamic link is not right because, when accessing a local variable of an enclosing function, we need to get the last activation of that enclosing function at the point where the nested function was called. The way to keep the last activation of the enclosing function is called static link in contrast to the dynamic link.

The static link is conceptually simple, it is also a chain of frame pointers like the dynamic link. In contrast to the dynamic link, which is always set the same way by the callee), the static link may be set differently depending on which function is being called and it will be set by the caller. Below we will see the exact rules.

Consider the following more contrived example;

void f(void) // non nested (nesting depth = 0)

{

int x;

void g() // nested (nesting depth = 1)

{

x = x + 1; // x ← x + 1

}

void h() // nested (nesting depth = 1)

{

void m() // nested (nesting depth = 2)

{

x = x + 2; // x ← x + 2

g(); // call g

}

g(); // call g

m(); // call m

x = x + 3; // x ← x + 3

}

x = 1; // x ← 1

h(); // call h

// here x will be 8

}

A function can, obviously, call an immediately nested function. So from the body of function f we can call g or h. Similarly from the body of function h we can call m. A function can be called by other (non-immediately nested) functions as long as the nesting depth of the caller is greater or equal than the callee. So from m we can call m (recursively), h, g and f. It would not be allowed that f or g called m.

Note that h and g are both enclosed by f. So when they are called, their dynamic link will be of course the caller but their static link must always point to the frame of f. On the other hand, m is enclosed by h, so its static link will point to the frame of h (and in the example, its dynamic link too because it is the only nested function inside h and it does not call itself recursively either). When m calls g, the static link must be again the frame of its enclosing function f.

Setting up a static link

Like it happens with the dynamic link, the AAPCS does not mandate any register to be used as the static link. In fact, any callee-saved register that does not have any specific purpose will do. We will use r10.

Setting up the static link is a bit more involved because it requires paying attention which function we are calling. There are two cases:

- The function is immediately nested (like when from

fwe callgorh, or when fromhwe callm). The static link is simply the frame pointer of the caller.

For theses cases, thus, the following is all we have to do prior the call.mov r10, fp bl immediately-nested-function - The function is not immediately nested (like when from

mwe callg) then the static frame must be that of the enclosing function of the callee. Since the static link forms a chain it is just a matter of advancing in the chain as many times as the difference of nesting depths.

For instance, whenmcallsg, the static link ofmis the frame ofh. At the same time the static link ofhis the frame off. Sincegandhare siblings, their static link must be the same. So whenmcallsg, the static link should be the same ofh.

For theses cases, we will have to do the followingldr r10, [fp, #X0] /* Xi will be the appropiate offset where the previous value of r10 is found Note that Xi depends on the layout of our stack after we have push-ed the caller-saved registers */ ldr r10, [r10, #X1] \ ldr r10, [r10, #X2] | ... | advance the static link as many times ... | the difference of the nesting depth ... | (it may be zero times when calling a sibling) ldr r10, [r10, #Xn] / bl non-immediately-nested-function

This may seem very complicated but it is not. Since in the example above there are a few functions, we will do one function at a time. Let's start with f.

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

f:

push {r4, r10, fp, lr} /* keep registers */

mov fp, sp /* setup dynamic link */

sub sp, sp, #8 /* make room for x (4 + 4 bytes) */

/* x will be in address "fp - 4" */

/* At this point our stack looks like this

Data | Address | Notes

------+---------+---------------------------

| fp - 8 | alignment (per AAPCS)

x | fp - 4 |

r4 | fp |

r10 | fp + 8 | previous value of r10

fp | fp + 12 | previous value of fp

lr | fp + 16 |

*/

mov r4, #1 /* r4 ← 1 */

str r4, [fp, #-4] /* x ← r4 */

/* prepare the call to h */

mov r10, fp /* setup the static link,

since we are calling an immediately nested function

it is just the current frame */

bl h /* call h */

mov sp, fp /* restore stack */

pop {r4, r10, fp, lr} /* restore registers */

bx lr /* return */

Since f is not nested in any other function, the previous value of r10 does not have any special meaning for us. We just keep it because r10, despite the special meaning we will give it, is still a callee-saved register as mandated by the AAPCS. At the beginning, we allocate space for the variable x by enlarging the stack (line 35). Variable x will be always in fp - 4. Then we set x to 1 (line 51). Nothing fancy here since this is a non-nested function.

Now f calls h (line 57). Since it is an immediately nested function, the static link is as in the case I: the current frame pointer. So we just set r10 to be fp (line 56).

Let's see the code of h now.

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

/* ------ nested function ------------------ */

h :

push {r4, r5, r10, fp, lr} /* keep registers */

mov fp, sp /* setup dynamic link */

sub sp, sp, #4 /* align stack */

/* At this point our stack looks like this

Data | Address | Notes

------+---------+---------------------------

| fp - 4 | alignment (per AAPCS)

r4 | fp |

r5 | fp + 4 |

r10 | fp + 8 | frame pointer of 'f'

fp | fp + 12 | frame pointer of caller

lr | fp + 16 |

*/

/* prepare call to g */

/* g is a sibling so the static link will be the same

as the current one */

ldr r10, [fp, #8]

bl g

/* prepare call to m */

/* m is an immediately nested function so the static

link is the current frame */

mov r10, fp

bl m

ldr r4, [fp, #8] /* load frame pointer of 'f' */

ldr r5, [r4, #-4] /* r5 ← x */

add r5, r5, #3 /* r5 ← r5 + 3 */

str r5, [r4, #-4] /* x ← r5 */

mov sp, fp /* restore stack */

pop {r4, r5, r10, fp, lr} /* restore registers */

bx lr

We start the function as usual, pushing registers onto the stack and setting up the dynamic link (lines 64 to 65). We adjust the stack so the stack pointer is 8-byte aligned because we have pushed an even number of registers (line 68). If you check the layout of the stack after this last adjustment (depicted in lines 72 to 79), you will see that in fp + 8 we have the value of r10 which the caller of h (in this example only f, but it could be another function) must ensure that is the frame pointer of f. This extra pointer in the stack is the static link.

Now the function calls g (line 86) but it must properly set the static link prior to the call. In this case the static link is the same as h because we call g which is a sibling of h, so they share the same static link. We get it from fp + 8 (line 85). This is in fact the case II described above: g is not an immediately nested function of h. So we have to get the static link of the caller (the static link of h, found in fp + 8) and then advance it as many times as the difference of their nesting depths. Being siblings means that their nesting depths are the same, so no advancement is actually required.

After the call to g, the function calls m (line 92) which happens to be an immediately nested function, so its static link is the current frame pointer (line 91) because this is again the case I.

Let's see now the code of m.

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

/* ------ nested function ------------------ */

m:

push {r4, r5, r10, fp, lr} /* keep registers */

mov fp, sp /* setup dynamic link */

sub sp, sp, #4 /* align stack */

/* At this point our stack looks like this

Data | Address | Notes

------+---------+---------------------------

| fp - 4 | alignment (per AAPCS)

r4 | fp |

r5 | fp + 4 |

r10 | fp + 8 | frame pointer of 'h'

fp | fp + 12 | frame pointer of caller

lr | fp + 16 |

*/

ldr r4, [fp, #8] /* r4 ← frame pointer of 'h' */

ldr r4, [r4, #8] /* r4 ← frame pointer of 'f' */

ldr r5, [r4, #-4] /* r5 ← x */

add r5, r5, #2 /* r5 ← r5 + 2 */

str r5, [r4, #-4] /* x ← r5 */

/* setup call to g */

ldr r10, [fp, #8] /* r10 ← frame pointer of 'h' */

ldr r10, [r10, #8] /* r10 ← frame pointer of 'f' */

bl g

mov sp, fp /* restore stack */

pop {r4, r5, r10, fp, lr} /* restore registers */

bx lr

Function m starts pretty similar to h: we push the registers, setup the dynamic link and adjust the stack so it is 8-byte aligned (lines 106 to 109). After this, we again have the static link at fp + 8. If you are wondering if the static link will always be in fp + 8, the answer is no, it depends on how many registers are pushed before r10, it just happens that we always push r4 and r5, but if we, for instance, also pushed r6 it would be at a larger offset. Each function may have the static link at different offsets (this is why we are drawing the stack layout for every function, bear this in mind!).

The first thing m does is x ← x + 2. So we have to get the address of x. The address of x is relative to the frame pointer of f because x is a local variable of f. We do not have the frame pointer of f but the one of h (this is the static link of m). Since the frame pointers form a chain, we can load the frame pointer of h and then use it to get the static link of h which will be the frame pointer of f. You may have to reread this last statement twice :) So we first get the frame pointer of h (line 122), recall that this is the static link of m that was set up when h called m (line 91). Now we have the frame pointer of h, so we can get its static link (line 123) which again is at offset +8 but this is by chance, it could be in a different offset! The static link of h is the frame pointer of f, so we now have the frame pointer f as we wanted and then we can proceed to get the address of x, which is at offset -4 of the frame pointer of f. With this address now we can perform x ← x + 2 (lines 124 to 126).

Then m calls g (line 131). This is again a case II. But this time g is not a sibling of m: their nesting depths differ by 1. So we first load the current static link (line 129), the frame pointer of h. And then we advance 1 link through the chain of static links (line 130). Let me insist again: it is by chance that the static link of h and f is found at fp+8, each function could have it at different offsets.

Let's see now the code of g, which is pretty similar to that of h except that it does not call anyone.

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

/* ------ nested function ------------------ */

g:

push {r4, r5, r10, fp, lr} /* keep registers */

mov fp, sp /* setup dynamic link */

sub sp, sp, #4 /* align stack */

/* At this point our stack looks like this

Data | Address | Notes

------+---------+---------------------------

| fp - 4 | alignment (per AAPCS)

r4 | fp |

r5 | fp + 4 |

r10 | fp + 8 | frame pointer of 'f'

fp | fp + 12 | frame pointer of caller

lr | fp + 16 |

*/

ldr r4, [fp, #8] /* r4 ← frame pointer of 'f' */

ldr r5, [r4, #-4] /* r5 ← x */

add r5, r5, #1 /* r5 ← r5 + 1 */

str r5, [r4, #-4] /* x ← r5 */

mov sp, fp /* restore dynamic link */

pop {r4, r5, r10, fp, lr} /* restore registers */

bx lr

Note that h and g compute the address of x exactly the same way since they are at the same nesting depth.

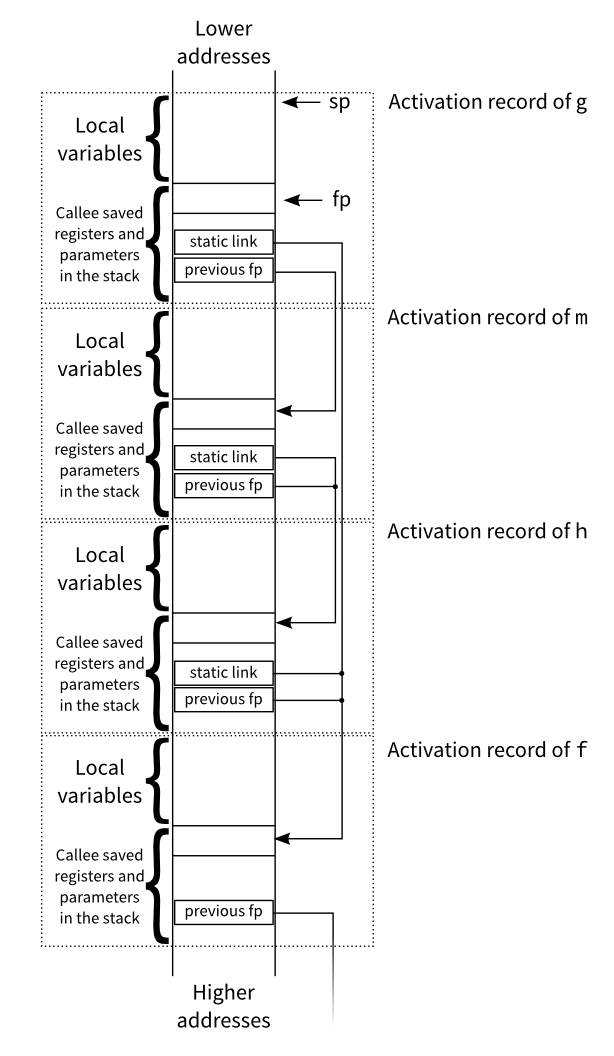

Below is a picture of how the layout looks once m has called g. Note that the static link of g and h is the same, the frame pointer of f, because they are siblings.

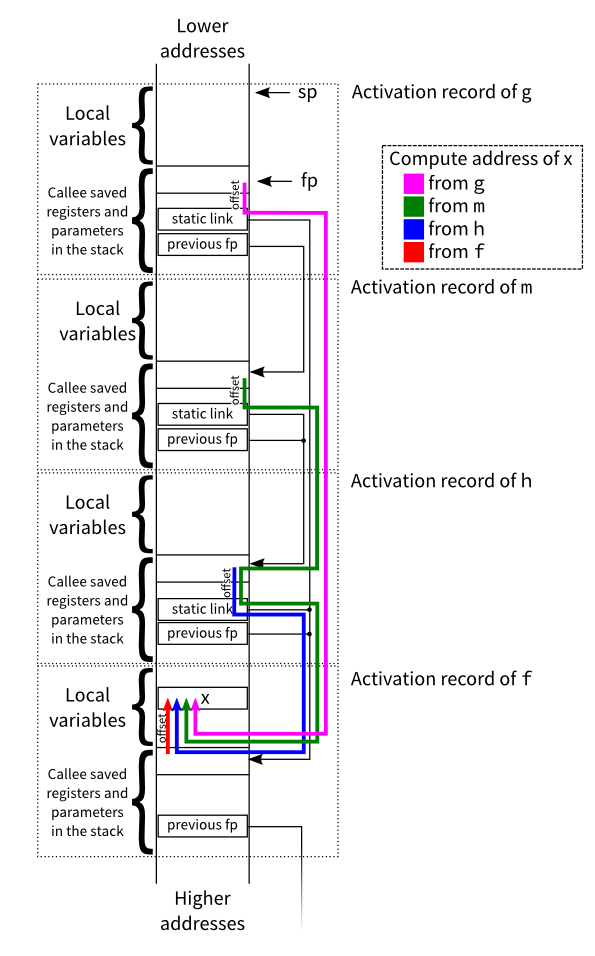

Below is the same image but this time using coloured lines to show how each function can compute the address of x.

Finally here is the main. Note that when a non-nested function calls another non-nested function, there is no need to do anything to r10. This is the reason why r10 does not have any meaningful value upon the entry to f.

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

.globl main

main :

push {r4, lr} /* keep registers */

bl f /* call f */

mov r0, #0

pop {r4, lr}

bx lr

Discussion

If you stop and think about all this stuff of the static link you may soon realize that there is something murky with all this nested functions business: we are passing some sort of hidden parameter (through r10) to the nested functions. In fact, we are somehow cheating, because we set r10 right before the call and then we push it at the entry of the nested functions even if they do not modify it in the called function. Why are we doing this seemingly useless step?

Well, by always pushing r10 in the stack, we are just covering up the naked truth: nested functions require a, somewhat hidden, extra parameter. This extra parameter is this static link thing. Sometimes it is also called the lexical scope. It is called the lexical scope because it gives us the context of the lexically (i.e. in the code) enclosing function (in contrast the dynamic scope would be that of our caller, which we do not care about unless we are a debugger). With that lexical context we can get the local variables of that enclosing function. Due to the chaining nature of the static link, we can move up the lexical scopes. This is the reason m can access a variable of f, it just climbs through the static links as shown in the last picture above.

Can we pass the lexical scope to a function using the stack, rather than a callee-saved register? Sure. For convenience it may have to be the first stack-passed parameter (so its offset from fp is easy to compute). Instead of setting r10 prior the call, we will enlarge sp as needed (at least 8 bytes, to keep the stack 8-byte aligned) and then store there the static link. In the stack layout, the static link now will be found after (i.e. larger offsets than) the pushed registers.

Can we pass the lexical scope using a caller-saved register (like r0, r1, r2 or r3)? Yes, but the first thing we should do is to keep it in the stack, as a local variable (i.e. negative offsets from fp). Why? Because if we do not keep it in the stack we will not be able to move upwards the static links.

As you can see, any approach requires us to keep the static link in the stack. While our approach of using r10 may not be completely orthodox ends doing the right thing.

But the discussion would not be complete if we did not talk about pointers. What about a pointer to a nested function? Is that even possible? When (directly) calling a nested function we can set the lexical scope appropiately because we know everything: we know where we are and we know which function we are going to call. But what about an indirect call using a pointer to a function? We do not know which (possibly nested) function we are going to call, how can we appropriately set its lexical scope. Well, the answer is, we cannot unless we keep the lexical scope somewhere. This means that just the address of the function will not do. We will need to keep, along with the address to the function, the lexical scope. So a pointer to a nested function happens to be different to a pointer to a non-nested function, given that the latter does not need the lexical scope to be set.

Having incompatible pointers for nested an non nested functions is not desirable. This may be a reason why C (and C++) do not directly support nested functions (albeit this limitation can be worked around using other approaches). In the next chapter, we will see a clever approach to avoid, to some extent, having different pointers to nested functions that are different from pointers to non nested functions.

That's all for today.